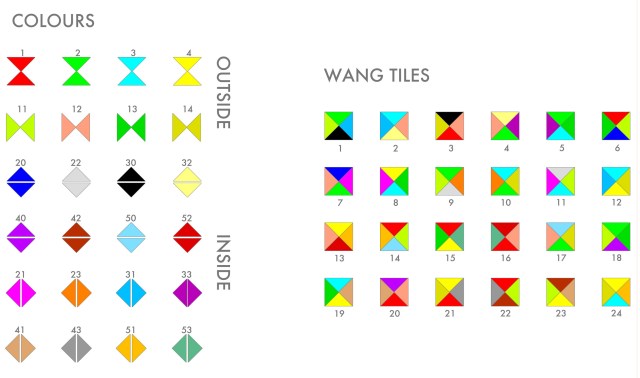

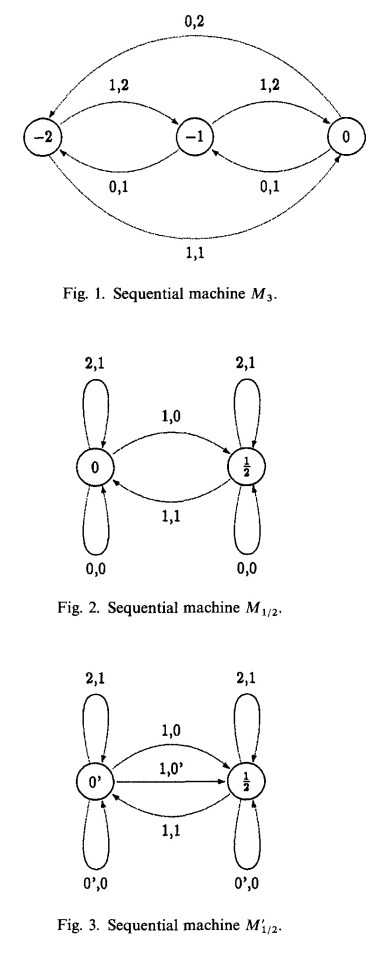

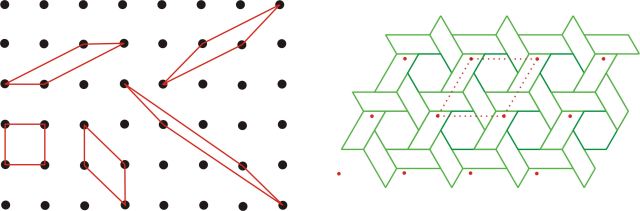

Wang pointed out that it is possible to find sets of Wang tiles that mimic the behaviour of any Turing Machine (Wang 1975).

A Turing machine can compute all recursive functions, that is functions whose values can be calculated in a finite number of steps. That is to do, however inefficiently, what any conceivable computer can do.

The basic idea is to use rows of tiles to simulate the tape in the machine, with successive rows corresponding to consecutive states of the machine.

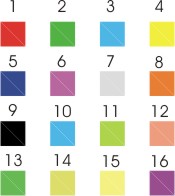

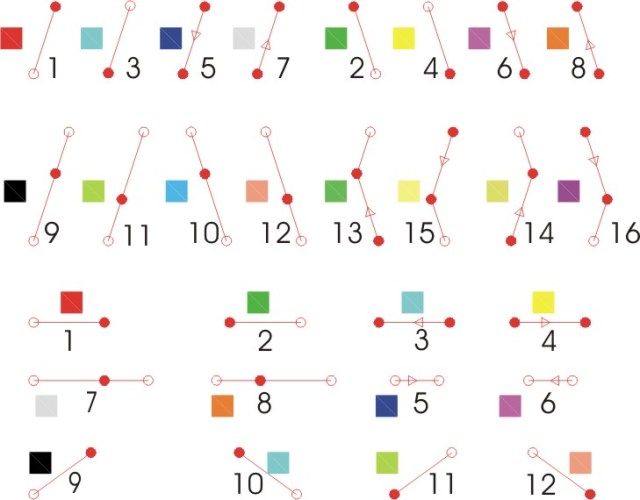

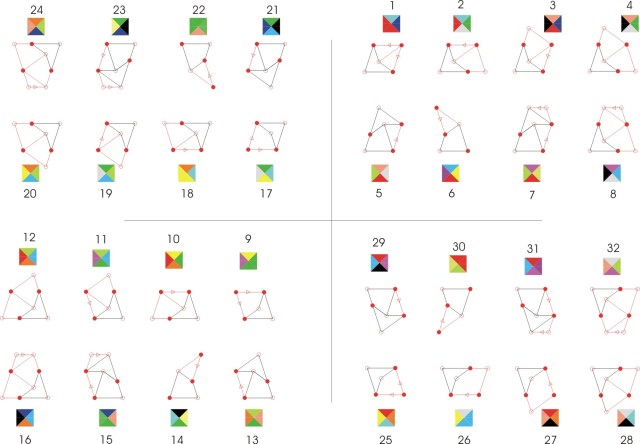

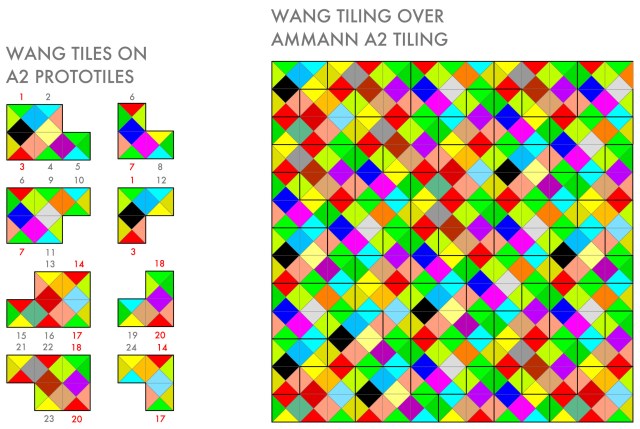

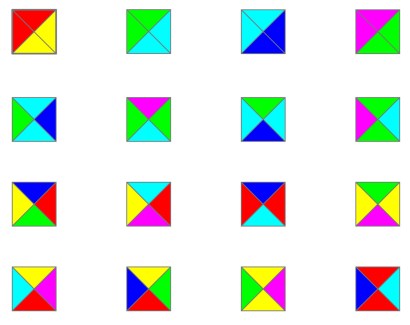

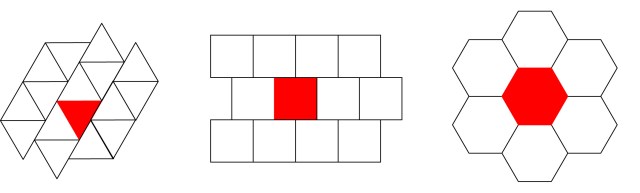

The following examples are based on those in “Tiling and Patterns” (Grünbaum and Shephard 1987) with coloured tiles replacing numbered tiles, and initialisation somewhat simplified.

Simple Addition Using Wang Tiles

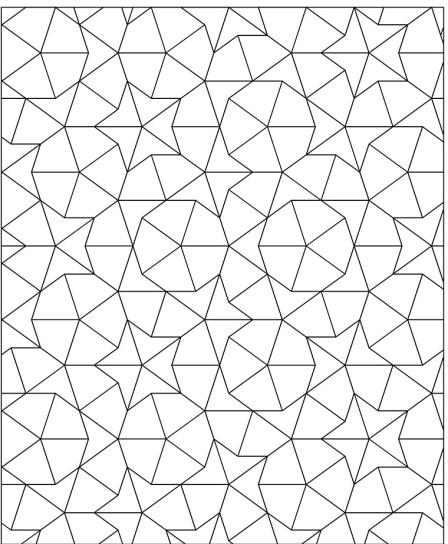

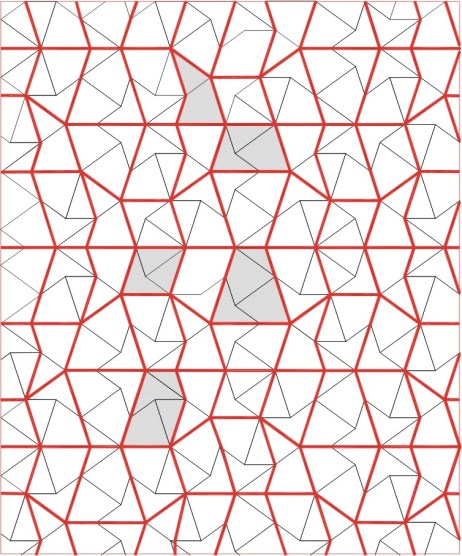

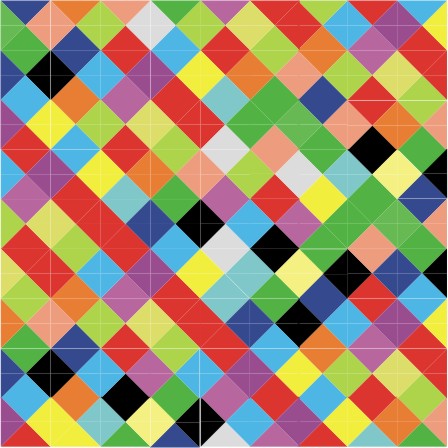

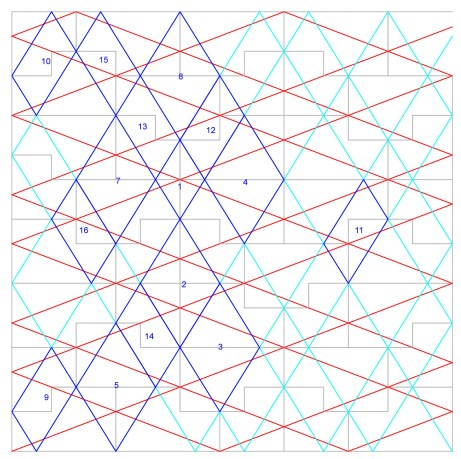

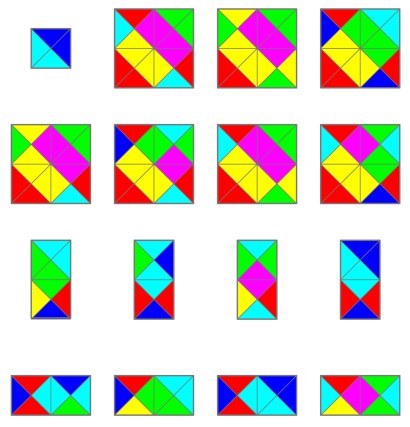

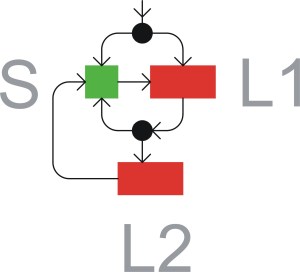

This example uses one quarter of the plane, bounded by grey tiles, it shows the addition of two positive integers, a and b, and for convenience it is assumed that 2 ≤ a < b.

In this slightly simplified presentation step 1 consists of placing tiles to indicate the numbers to be added together (5 and 9 in this case) and a start signal in the top left-most square.

Step 2 then consists of adding the only possible tiles next to those that have already been placed and step 3 shows the signal beginning to take a diagonal path downwards. This continues, using tiles from column B, until it meets the tiles descending from the first number, with tiles from column C. At the meeting point a series of horizontal tiles, from column D, is generated which changes direction when it meets the tiles descending from the second number. The signal then moves diagonally upwards, using tiles from column F, until the process terminates at the top edge where its position indicates the required answer.

The colour numbers above are those used by Grünbaum and Shephard and the tiles are the same except that a missing one has been added and the tiles have been arranged in a slightly different manner. Incidentally using coloured tiles rather than numbered ones meant that the missing tile was much easier to spot.

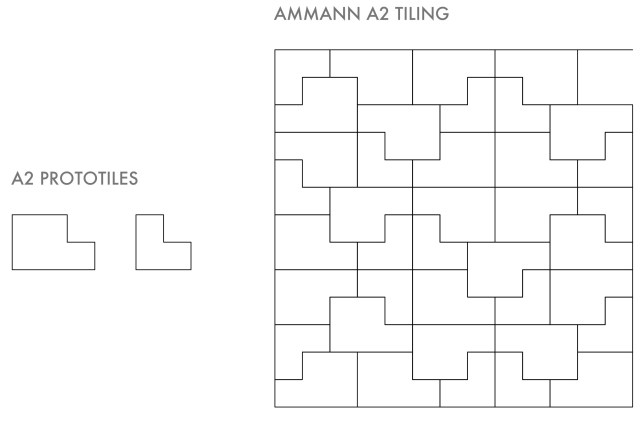

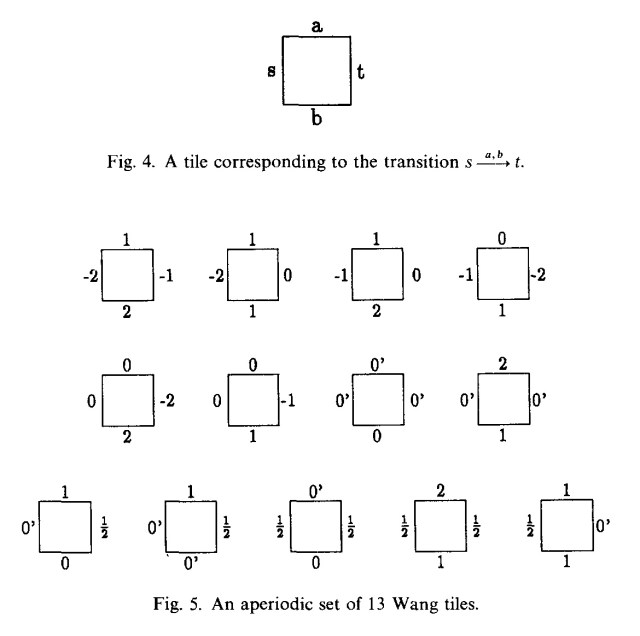

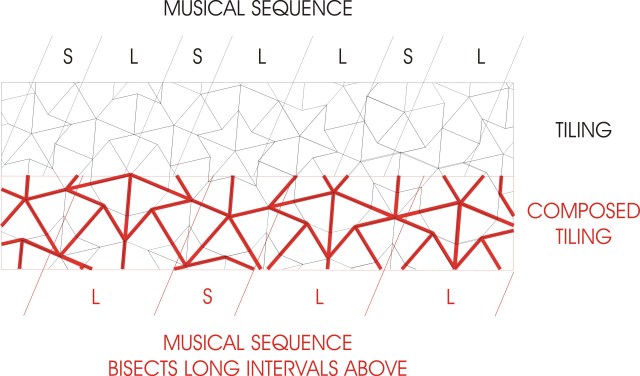

Generating the Fibonacci Sequence

The following example is presented without a complex narrative. It shows all the steps on one diagram, follows a similar method to the previous example and is otherwise I think self explanatory.

Diagram above corrected 08/05/2015

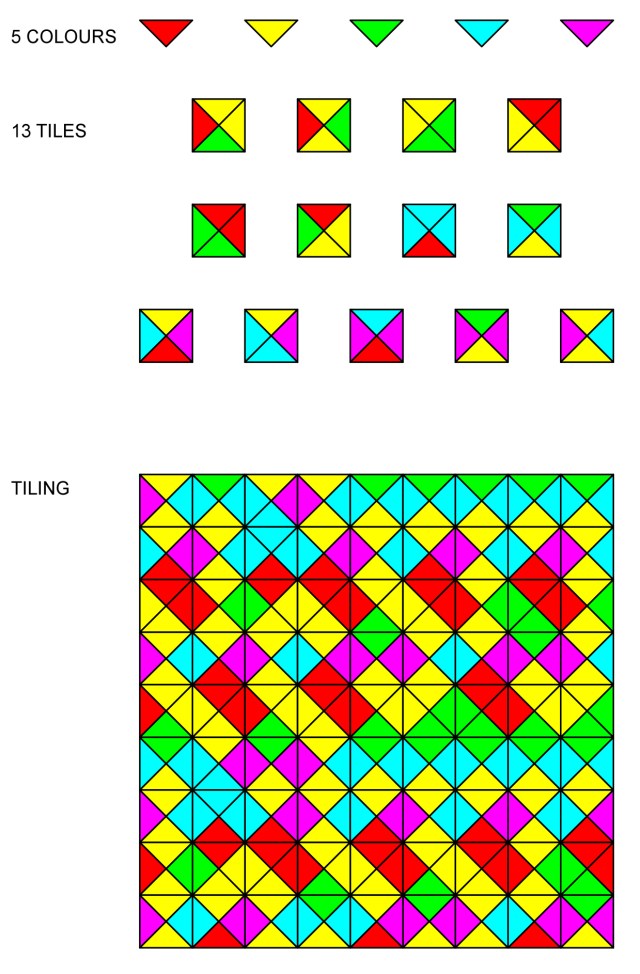

Generating Prime Numbers

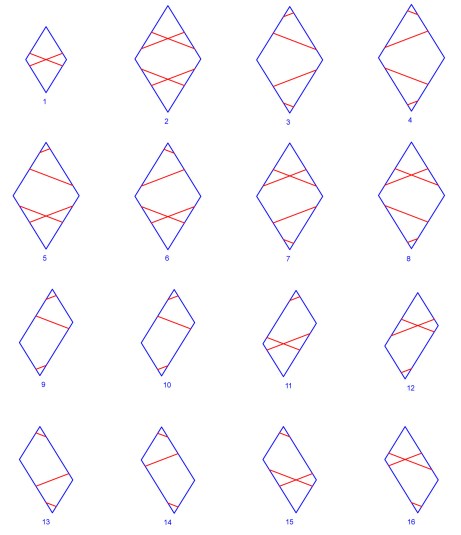

The final example illustrates the ingenuity that can be required to carry out some computations, it is due to E. F. Moore and M. Fieldhouse and was communicated to Grünbaum and Shephard by H. Wang. Here the only change I have made is to use colours rather than colour numbers.

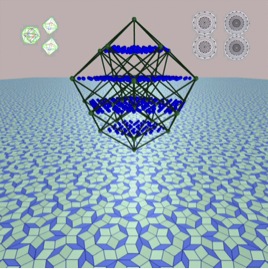

The tiling uses 30 prototiles and forces a tiling that places tiles marked P or C at the prime and composite positions in the top row. The tiles are marked with letters as well as being coloured and it can be seen that they build up blocks of squares which increase in size downwards. These square blocks are indicated by thickened lines.

The tiles marked by an asterisk are used to generate the blocks down the left boundary and the tiles with superscript C transmit a signal to the effect that the number is composite. These composite signals are generated by the tiles by B* (which is only used once) and D4 (which occurs on the top right corner of each square block that does not abut on the left boundary of the tiling). They are absorbed by the tiles C on the top line, and D6 on the bottom right corner of certain blocks. When the signal is absorbed in this way it is regenerated higher up by a D4.

The increasing blocks signal to the top row when a number has a proper divisor greater than 2. Divisibility by 2 is taken care of by alternating A and B tiles in the second row. Either can transmit the composite signal. The special tile B* is introduced simply to ensure that a prime tile P appears in position 2. This does however seem to introduce a degree of circularity.

The use of colours again revealed an error in the designation of one edge of the bottom right tile in the tile set.