How Space Begins: Georges Perec

This is an extract from The Page the first essay in Georges Perec’s Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, Perec (1974, 1997).

“This is how space begins, with words only, signs traced on the blank page. To describe space: to name it, to trace it, like those portolano-makers who saturated the coastlines with the names of harbours, the names of capes, the names of inlets, until in the end the land was only separated from the sea by a continuous ribbon of text. Is the aleph, that place in Borges from which the entire world is visible simultaneously, anything other than an alphabet? Space as inventory, space as invention. Space begins with that model map in the old editions of the Petit Larousse Illustré, which used to represent something like 65 geographical terms in 60 sq. cm., miraculously brought together, deliberately abstract. Here is the desert, with its oasis, its wadi and its salt lake, here are the spring and the stream, the mountain torrent, the canal, the confluence, the river,……”

This is the illustration Perec is referring to.

The original is really small, only 6 x 10 cm, yet within this tiny area a complete field of interest (Géographie) is enumerated with labels and graphical representations tightly bound together. For instance the label Isthme is right next to its graphical representation and in a wholly natural relation to a Péninsule. In addition all the graphical representations are connected and arranged so as to form a plausible map.

As such it is a member of a very limited class of object, one that as far as I know does not have a name. Following Perec’s alphabetic suggestions, it seems appropriate to call this class of object a visual pangram.

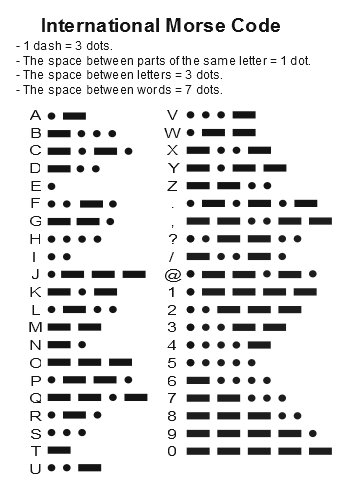

Pangrams use every letter of the alphabet at least once in a more or less meaningful sentence, for instance: –

Jackdaws love my big sphinx of quartz

This includes all 26 letters of the alphabet and has 5 reuses of letters (a twice, s, i and o).

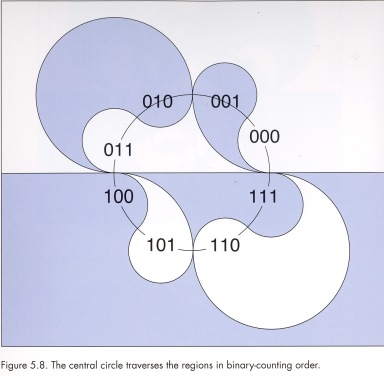

The suggested formulation is;-

that alphabet corresponds to an enumeration of a field of interest

and sentence to a pictorial representation of that field.

A Portolano Map

As noted in the Perec extract above, in a portolano map the text threatens to overrun the graphical image (the coastline) as in this 14th century portolano style map of the Mediteranean.

Anonymous nautical chart in portolan style probably drawn in Genoa

c. 1320-1350.Library of Congress

Anonymous nautical chart in portolan style probably drawn in Genoa

c. 1320-1350.Library of Congress

The Aleph and the Successive Nature of Language

Aleph is the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet and the first letter of the Hebrew word for infinity. Aleph numbers are therefore used to indicate the cardinality (the size) of infinite sets starting with the smallest Aleph-null. Hence the title of the Borges story is The Aleph.

“How, then, can I translate into words the limitless Aleph, which my floundering mind can scarcely encompass? Mystics, faced with the same problem, fall back on symbols: to signify the godhead, one Persian speaks of a bird that somehow is all birds; Alanus de Insulis, of a sphere whose center is everywhere and circumference is nowhere; Ezekiel, of a four-faced angel who at one and the same time moves east and west, north and south. (Not in vain do I recall these inconceivable analogies; they bear some relation to the Aleph.)

Perhaps the gods might grant me a similar metaphor, but then this account would become contaminated by literature, by fiction. Really, what I want to do is impossible, for any listing of an endless series is doomed to be infinitesimal.

In that single gigantic instant I saw millions of acts both delightful and awful; not one of them occupied the same point in space, without overlapping or transparency. What my eyes beheld was simultaneous, but what I shall now write down will be successive, because language is successive. Nonetheless, I’ll try to recollect what I can.”

Text and Image

In the portolano map the text overpowers the graphical image (the coastline).

In the Aleph story, an infinite and all pervading moving image – a premonition of multi-channel television or the internet perhaps, seriously distracts the author and prevents him from writing; a state of affairs that is only resolved by the writer demolishing his house and filling the basement, where the Aleph resides, with concrete.

But in the Petit Larousse Illustré map, and in visual pangrams in general, image and text are simultaneous and reinforce each other, without either threatening to dominate the other.

Aiding Memory

There is some evidence that sequential and visual information are processed in different ways, and that recall is better with a combination of text and image. Mental Representations A Dual Coding Approach. Paivio (1990).

Indeed in Species of Spaces Perec is remembering, in a piece he wrote in the 1970s, something he must have read and seen as a child in the 1940s.

Making a Visual Argument

This visual pangram attempts to show how John Soane’s architecture is related to (and is distinct from) all other architectural styles.

It represents the styles of architecture as a park one can walk round; inspecting buildings of MAHOMEDAN POINTED, CHRISTIAN POINTED, GOTHIC etc. styles. Each style is enclosed in its own fenced off area and labelled in an uppercase sans-serif typeface then a new re-invention, described in The Nymph and the Grot, Mosley (1969).

There is a straight path from the park gate to the Palace of Architecture. The Soanean building is nearest to the Palace of Architecture in the Greco-Roman section, with its own path to the Palace but carefully screened and separated from the Gothic. The Egyptian section also has its own path but all the other styles are accessed from meandering paths that branch off from the main route to the Palace of Architecture.

A visual pangram is being used to help make a visual argument.

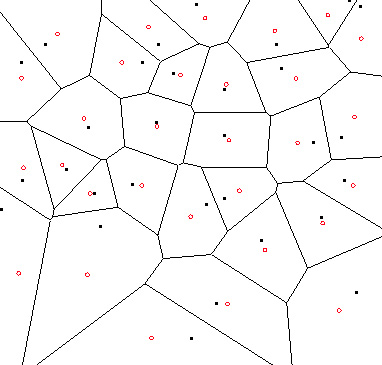

An Indexed Visual Pangram

This image forms the front endpaper and frontispiece of the Third Edition of A Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe and shows the birds one is most likely to see in the places where they are most likely to be seen (from top to bottom) on telephone wires, in trees, on fence posts or on the ground. Peterson, Mountford, and Hollom (1974).

The indexing tidies up the overall pictorial image but gives prominence to the individual graphical representations at the expense of the labels. This is emphasised somewhat by the skylark silhouette being allowed to overlap the text panel. It also imposes an arbitrary, if accidental, linear order on the overall image; top-left to bottom-right, 1 to 20, BEE-EATER to ROOK.

Visual List or Confection: Pugin’s Churches

Edward Tufte used this image as an example of what he called a visual list or confection. It is the frontispiece of Pugin’s An Apology for The Revival of Christian Architecture in England. Pugin (1843).

It shows St Giles Cheadle in the centre surrounded by other Pugin projects (some of them never completed).

Many other examples of visual lists or confections are also frontispieces that act as visual indexes and otherwise advertise a book’s contents.

The image above does in fact contain minute unreadable index numbers.

These refer to a list of the illustrated churches but the list is conveniently located some six pages into the book.

Advertisement: John Soane’s Models

This 1818 rendering by Joseph Michael Gandy is over modestly titled Perspective of various designs for public and private buildings executed by John Soane between 1780 and 1815, shown as if they were models in a gallery.

The image was used as the front and back endpapers of Gillian Darley’s John Soane: An Accidental Romantic. Darley (1990)

There is no attempt to label or index any of the models and as with the Pugin etching, this wonderful rendering is more advertisement than useful reference or thinking tool.

Interactive Visual Pangram

This is an example of a visual pangram being used as an interface to the planning regulations.

It can be tried out here http://www.planningportal.gov.uk/permission/house

Interesting to think how this might be done with a ‘modern’ house; would it, could it, mean as much?

Bibliography

Perec, G. (1974 / 1997). Espèces d’espaces (Species of Spaces and Other Pieces). (Sturrock, J., Trans.) Paris: Galilée / Penguin. Borges, J.L. (1947). El Aleph (Di Giovanni, N. T., Trans with author) Larousse. (1912). Petit Larousse Illustré; Librairie. Paris: Larousse. Paivio, A. (1990) Mental Representations A Dual Coding Approach. Oxford Peterson, R., Mountford, G and P. A. D. Hollom, P. A. D. (1974) A Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe Third Edition; Collins Wightwick, G. (1840) The Palace of Architecture (‘a romance of art and history’) The Gentleman’s Magazine Mosley, J. (1965). The Nymph and the Grot St Bride Library. http://typefoundry.blogspot.com/2007/01/nymph-and-grot-update.html Gandy J. M. (1818) Perspective of various designs for public and private buildings executed by John Soane between 1780 and 1815, shown as if they were models in a gallery Darley, G. (1999) JOHN SOANE: an accidental romantic Yale University Press Pugin A.W.N. (1843) An Apology for The Revival of Christian Architecture in England. London Tufte, E. R. (1997) Visual Explanations Images and Quantities, Evidence and Narrative Graphics Press, Cheshire Conn.